By Seth Thomas Gulledge | Photos by Juliette Cooke

Greenville Magazine Fall 2017 article (republished with permission)

According to the Greenville Utilities Commission, people flush some weird things down their toilets, let strange things go down the drain and even find a way to put down-right odd things in manholes.

Jason Manning, the GUC wastewater treatment plant superintendent, attributes this to the perspective of the average citizen.

"For them, it's just out-of-sight, out-of-mind," Manning said. "They just put it in the toilet, and it's gone forever."

The problem, though, is that most of the objects are far from being gone and continue to wreak havoc on the city's plumbing. For the maintenance crews at GUC, these problems are very much in-sight, in-mind and definitely in-smell.

Almost every morning around 8 a.m., a three-man crew goes out to the pump stations throughout Greenville to clean out the filters and clean clogs in the pumps. The problem is so common that cleaning them out is just a daily maintenance task for workers.

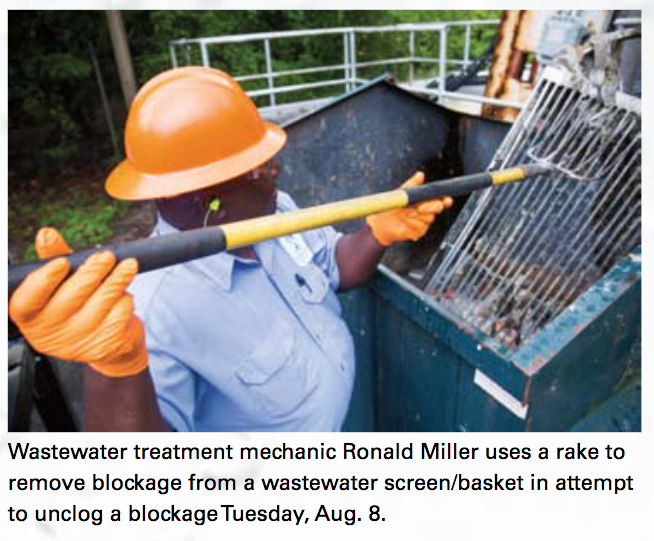

Ronald Miller, Corey Mills and Tripp Leggett work together as a crew Tuesdays through Fridays. Starting their day at 7 a.m., they work on a variety of tasks throughout a nearly 11-hour shift.

Miller, a 14-year veteran of GUC, said that cleaning out these filters is the worst thing they have to do on a regular basis. It's not hard to explain why.

Approaching the pump station, the crew first backs up their truck to a pump outside, then uses the crane on the truck to lift a basket out of the ground and over a dumpster. The basket works as a screen, theoretically catching most of the debris that ends up in the line before the sewage reaches the pumps.

After just one day since the last cleaning, the crew still pulled a mostly full basket, dripping with sewage and assorted items.

With the basket hanging over the dumpster, a crew member used a pitchfork to dislodge all of the debris before returning it into the ground.

With the basket hanging over the dumpster, a crew member used a pitchfork to dislodge all of the debris before returning it into the ground.

This process smells exactly like it sounds, and each member of the crew put on a new pair of gloves at least once or twice during the task.

"It's definitely not my favorite part of my job," Miller said. "But it's not so bad once you get used to it."

What would make the dirty job just a bit easier?

Each crew member gave the same answer: no more "flushable wipes."

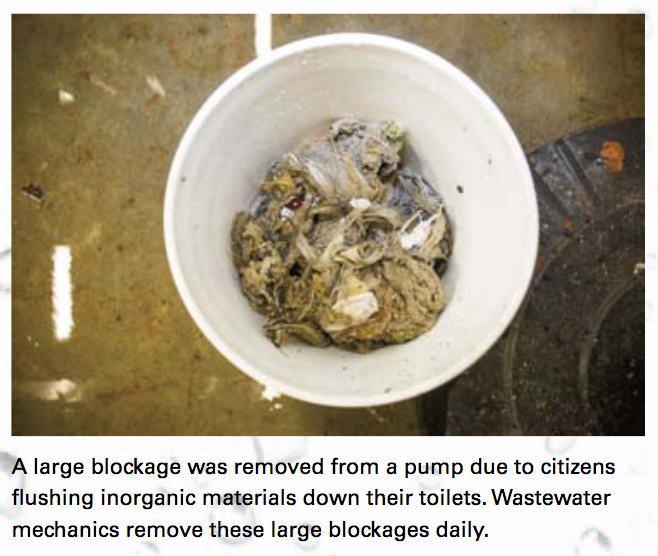

Miller said there is no such thing as a flushable wipe, even though it may be advertised as such and may make it through the individual homeowner's plumbing. But the wipes almost certainly create massive clogs in the GUC system.

The majority of the debris that must be dislodged? You guessed it: "flushable" wipes. The rest can be difficult to identify by the time the crews get to it, but Miller said they find a lot of the expected, including feminine hygiene products, condoms, plastic debris — all items people likely know shouldn't be flushed, but sure, makes sense.

But then there's the unexpected and unexplainable.

Crews have found household garbage, dead animals, towels, and even money. Once, Miller said, he found part of a brick.

"Basically, anything they can flush down a commode, they're going to flush down a commode," he said.

"Basically, anything they can flush down a commode, they're going to flush down a commode," he said.

Fortunately, most of that debris is caught before it moves into the much more delicate and complex pumps. But that's not the case for the wipes, which cannot always be held off by the pitchfork-to-basket practice — and that means someone has to unclog the pumps.

The crew descends into an underground portion of the basement, working in a small, concrete room that doesn't have nearly as much fresh air as one might hope.

They open a valve, releasing the clog and all of the sewage it was impeding onto the floor of the room.

It's difficult for the crew to say which is worse: the smell of a room more than an inch deep in raw sewage or the visual of a sewage river running into the corner drain. Regardless, they work in it for around a half hour, if everything goes as planned. Miller said things typically go the other way.

That prediction was fulfilled during Greenville Magazine's visit, guaranteeing the crew some more quality time in the sewage-filled room.

Still, the crew seems unaffected by the entire process, joking and laughing with one another and remaining in high spirits throughout their work. They said they became used to the smell a long time ago.

The crew members said that overall they love their jobs — after all, someone has to do the dirty work — though they prefer that residents stop flushing weird things down their toilets.

Manning said that if Greenville residents could adapt their behavior, it could keep some money from going down the drain.

By lowering the amount of debris in the system, GUC's operational cost would lower, and the amount of time and energy used to maintain these systems would plummet. In turn, this would likely decrease utility bills for residents across the city.

Until that day though, crews like Leggett, Mills and Miller will continue their morning ritual, smiling and doing this invaluable work for the city, literally up to their ankles in the problem.

"You just gotta have waterproof boots," Miller said. "That's the most important part."